Why Are MLS Stadiums So Small?

Have you ever wondered why Major League Soccer stadiums are so small?

It seems kind of odd if you look back at history. Back in the late 1970s, attendance at NASL matches was actually pretty high. Take 1978, for example:

With an average home attendance of over 47,000, the New York Cosmos were one of the biggest drawing clubs in the world. And the Minnesota Kicks drew quite a few people at old Metropolitan Stadium.

In contrast, look at the current list of the largest MLS stadiums:

Note, though that 3 of the top 6 are multipurpose stadiums. If we look at only the “soccer-specific stadiums” we get a different picture:

So what’s going on? Was the NASL just that much more popular than the MLS? Or is something else happening?

Well, we’ve got to start with the difference between stadium culture in the United States and in England (as well as the rest of Europe).

Most professional level stadiums in the United States were baseball stadiums. For years, professional football teams played in local major league baseball stadiums during the winter.

There were stadiums designed specifically for American football, though these tended to be college football stadiums. Some of them, such as the Los Angeles Coliseum, are absolutely huge, and are still in use today.

Now, the beginnings of the NASL coincided with an era of building multipurpose stadiums. We tend to think of those as “cookie cutter” stadiums. Many of them were round in shape, and were designed to be less than perfect places to watch either baseball or American football.

Most of these stadiums were built by local governments, not by individual teams. The idea was to have a central location where most major local professional sports could be watched. In theory, the cities would benefit from a percentage of the gate receipts, though this was not always the case in practice.

This is a pretty big contrast to the history of stadiums in England, most of which were owned by local clubs. While the classic baseball stadiums rotted and fell into disrepair at a rate similar to the English stadiums, they were for the most part abandoned in the 1950s.

In fact — the abandonment of those old stadiums for new municipality-built arenas came about precisely because of the monopolistic nature of American sports leagues.

Teams could — and did — threaten their cities to move if they weren’t given new stadiums and sweetheart deals. Some teams did move to greener pastures in the end, such as the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants. Once the cities realized that the teams (and leagues) were serious, these publicly financed cookie cutter stadiums became reality.

The vast majority of NASL teams played in multipurpose facilities.

A lot of those stadiums had artificial turf. Many of them had tremendous maximum capacities for soccer. And most of them wound up being empty.

Even Giants Stadium, home to the famous New York Cosmos, often wasn’t sold out. In fact, with a maximum capacity of over 80,000, those impressive crowds of 47,000 or more meant that over 2/3 of the stadium was empty.

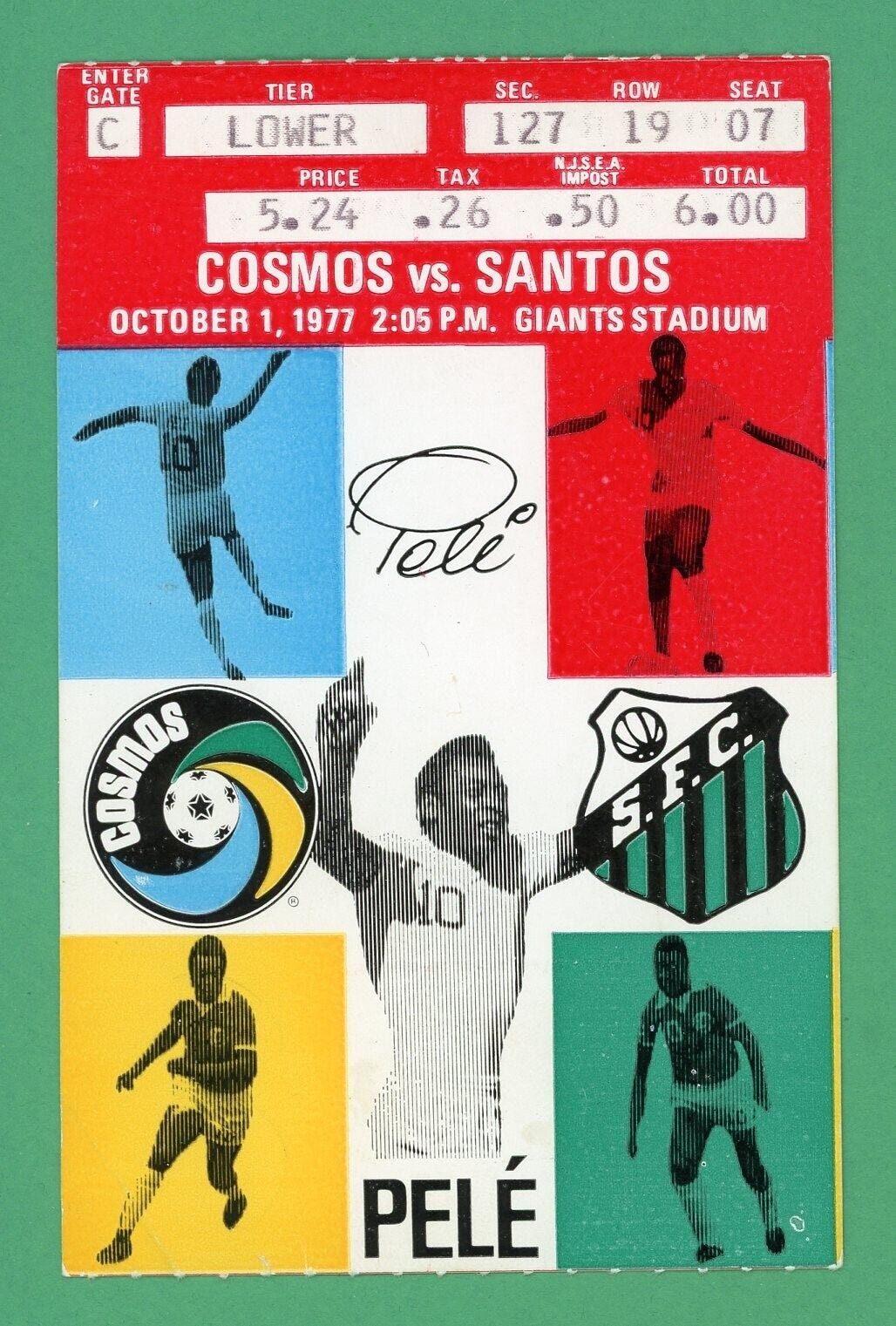

And it’s not like the Cosmos were raking in the cash, either. A lower bowl seat to an October 1 exhibition game against Santos — Pele’s last game — sold for $6:

Interestingly a mezzanine seat to the same match was more expensive:

This might be because the mezzanine view was better than the lower bowl view.

Meanwhile, third deck seating was likely even less expensive. This stub is from 1980, but it gives you an idea:

It’s also not exactly clear how much of the attendance at these matches came from free tickets. If you remember my brief article on the extremely obscure Utah Golden Strikers of the ASL, reports had it that their large first match attendance was mostly because the team gave away a ton of tickets:

Now, most soccer fans will tell you that MLS stadiums offer nice sight lines and an intimate atmosphere. They do, as a matter of fact — at least they are superior to watching a game in a converted American football stadium.

However, the truth is that the current stadiums are smaller because that is precisely where the demand for the sport seems to be at.

If that demand rises — and I’m sure it will — we may eventually see the day when MLS stadiums start hitting capacities of 50,000 or more.